Original story by John Thistleton, Canberra Times

Along the bottom of the beautiful Murrumbidgee gorge south of Canberra science is turning up the heat on huge carp.

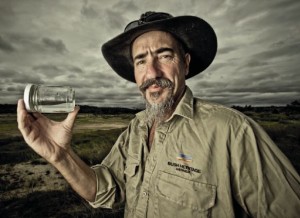

Senior fisheries technician Prue McGuffie of the NSW Department of Primary Industries with a carp that didn’t get away. Photo: Jay Cronan

In the first project to track carp in an upland river system in NSW, data will be gathered to learn seasonal migration patterns and the best opportunities to trap large numbers of aggregating carp.

Using fine nets and electro fishing, researchers gathered in carp, cod and freshwater prawns on Tuesday.

Acoustic tags were inserted into some of the big carp, which were released back into the eight-metre-deep hole at Bush Heritage Australia’s ”Scottsdale” reserve.

The tag sends out a ping to a listening station in a white buoy in the river. Every time a tagged fish passes, the station records a ping, enabling researchers to download information every few months.

Other carp were dissected to remove their ear bone to determine their age, a key to analysing population structure and determining good years of spawning.

Senior NSW Fisheries technician Prue McGuffie, who netted the hulking, slimy green and grey carp, also kept a watch out for endangered Macquarie perch, which she is researching.

Ms McGuffie netted two cod fingerlings that she will genetically test to determine if they are Murray cod or trout cod.

Meanwhile, on the banks with varying vested interests, scientists, a fly fisherman and a potato farmer’s son watched intensely as a four-kilometre stretch of the river was netted.

Fisherman Steve Samuels is providing local knowledge for the project, and can recount the 1970s when the Murrumbidgee teemed with spawning silver perch. ”You’d only see one or two carp,” he said. ”Trout were all the way up the river.”

Laurence Koenig, whose family grows organic garlic and potatoes on ”Ingelara” next door to Scottsdale, was there to collect dead carp, humanely dispatched in a tub of ice.

Mr Koenig hopes researchers will continue to catch carp from the big hole. It could give him a tonne of fertiliser at each trapping session.

University of Canberra ecologist Mark Lintermans netted the hole overnight for juvenile Macquarie perch, but came up empty-handed.

”They are a long-lived species, so that is not a problem; it just means they have missed a year,” Dr Lintermans said.

Bush Heritage regional manager Peter Saunders said data would determine the best carp removal and control options to safeguard native fish. “We hope this work will fill a gap in Australia’s understanding of carp biology and behaviour in upland river systems, and guide new trials for targeted carp removal to better protect our native fish and river habitats,” he said.

Dr Lintermans said that if carp moved broadly along the river, trapping may not be effective. If they stayed in one spot, they could be controlled.

Observations so far show carp will jump barriers like waterfalls, whereas native fish will not. Carp will congregate in warmer pockets of the river and, at other times, for bait feeding or spawning. Dr Lintermans said Murray cod were rare in that section of the river.

Original story by Tom Rayner, Charles Darwin University and Richard Kingsford at The Conversation