Media release by Tom Rickey, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Fish-friendly hydropower is the goal of international team

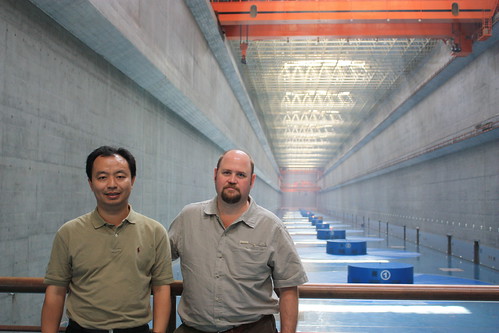

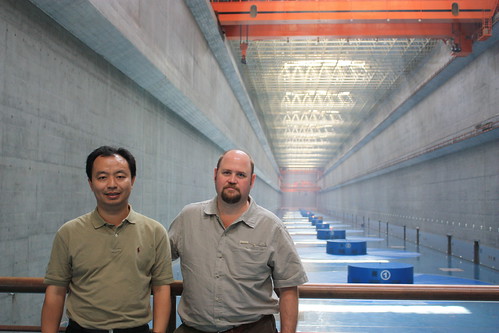

Zhiqun (Daniel) Deng (l) and Rich Brown in the Three Gorges Dam in China.

Think of the pressure change you feel when an elevator zips you up multiple floors in a tall building. Imagine how you’d feel if that elevator carried you all the way up to the top of Mt. Everest — in the blink of an eye.

That’s similar to what many fish experience when they travel through the turbulent waters near a dam. For some, the change in pressure is simply too big, too fast, and they die or are seriously injured.

In an article in the March issue of the journal Fisheries, ecologists from the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and colleagues from around the world explore ways to protect fish from the phenomenon, known as barotrauma.

Among the findings: Modifying turbines to minimize dramatic shifts in pressure offers an important way to keep fish safe when passing through dams. The research is part of a promising body of work that aims to reduce such injuries by improving turbine designs in dams around the world.

PNNL researchers are working with officials and scientists from Laos, Brazil, and Australia — areas where hydropower is booming — to apply lessons learned from experience in the Pacific Northwest, where salmon is king and water provides about two-thirds of the region’s power. There, billions of dollars have been spent since 1950 to save salmon endangered largely by the environmental impact of hydropower.

Colorized photo of the swim bladder of a smallmouth bass.

“Hydropower is a tremendous resource, often available in areas far from other sources of power, and critical to the future of many people around the globe,” said Richard Brown, a senior research scientist at PNNL and the lead author of the Fisheries paper.

“We want to help minimize the risk to fish while making it possible to bring power to schools, hospitals, and areas that desperately need it,” added Brown.

Harnessing the power of water flowing downhill to spin turbines is the most convenient energy source in many parts of the world, and it’s a clean, renewable source of energy to boot.

In Brazil, several dozen dams are planned along the Amazon, Madeira and Xingu rivers — an area that teems with more than 5,000 species of fish, and where some of the largest hydropower projects in the world are being built. In southeastern Australia, hydropower devices are planned in the area drained by the Murray-Darling river system. And in Southeast Asia, hundreds of dams and smaller hydro structures are planned in the Lower Mekong River Basin.

The authors say the findings from a collaboration that spans four continents improve our understanding of hydropower and will benefit fish around the globe. New results about species in the Mekong or Amazon regions, for instance, can inform fish-friendly practices in those regions of the United States where barotrauma has not been extensively studied.

To ‘Everest’ and back in an instant

Dams vary considerably in the challenges they pose to migrating fish, and the challenges are magnified when a fish must pass through more than one dam or hydro structure. At some, mortality is quite high, while at others, such as along the Columbia River, most fish are able to pass over or through a single dam safely, thanks to extensive measures to keep fish safe. Some fish spill harmlessly over the top, while others pass through pipes or other structures designed to route fish around the dam or steer them clear of the energy-producing turbines.

Researcher John Stephenson observes young salmon in a chamber used to simulate the conditions that fish sometimes experience as they travel through a dam.

Still, at most dams, the tremendous turbulence of the water can hurt or disorient fish, and the blades of a turbine can strike them. The new study focuses on a third problem, barotrauma — damage that happens at some dams when a fish experiences a large change in pressure.

Depending on its specific path, a fish traveling through a dam can experience an enormous drop in pressure, similar to the change from sea level to the top of Mt. Everest, in an instant. Just as fast, as the waters swirl, the fish suddenly finds itself back at its normal pressure.

Those sudden changes can have a catastrophic effect on fish, most of which are equipped with an organ known as a swim bladder — like a balloon — to maintain buoyancy at a desired depth. When the fish goes deeper and pressures are greater, the swim bladder shrinks; when the fish rises and pressure is reduced, the organ increases in size.

For some fish, the pressure shift means the swim bladder instantly expands four-fold or eight-fold, like an air bag that inflates suddenly. This rapid expansion can result in internal injuries or even death.

Factors at play include the specific path of a fish, the amount of water going through a turbine, the design of the turbine, the depth of water where the fish usually lives, and the physiology of the fish itself.

“To customize a power plant that is the safest for the fish, you must understand the species of fish in that particular river, their physiology, and the depth at which they normally reside, as well as the tremendous forces that the fish can be subjected to,” said Brown.

PNNL scientists have found that trying to keep minimum pressure higher in all areas near the turbine is key for preventing barotrauma. That reduces the amount of pressure change a fish is exposed to and is a crucial component for any turbine that is truly “fish friendly.” Preventing those extremely low pressures also protects a turbine from damage, reducing shutdowns and costly repairs.

Chinook salmon

Lower Mekong River Basin

Brown and PNNL colleague Zhiqun (Daniel) Deng have made several trips to work with scientists in Southeast Asia, where dozens of dams are planned along the Mekong River and its tributaries. The Mekong starts out high in Tibet and travels more than 2,700 miles, touching China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The team estimates more than 1,200 species of fish make their home in the Mekong, including the giant Mekong catfish and the giant freshwater stingray, as well as the endangered Irrawaddy dolphin.

The scientists estimate that the region’s fish account for almost half of the protein in the diet of the people of Laos and nearly 80 percent for the people of Cambodia. Four out of five households in the region rely heavily on fish for food, jobs, or both.

“Many people in Southeast Asia rely on fish both for food and their livelihood; it’s a huge issue, crucial in the lives of many people. Hydropower is also a critical resource in the region,” said Deng, a PNNL chief scientist and an author of the paper.

“Can we reduce the impact of dams on fish, to create a sustainable hydropower system and ensure the food supply and livelihoods of people in these regions? Can others learn from our experiences in the Pacific Northwest? This is why we do research in the laboratory — to make an impact in the real world, on people’s lives,” added Deng.

The same team of scientists just published a paper in the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, focusing broadly on creating sustainable hydro in the Lower Mekong River Basin. The paper discusses the potential for hydropower sources in the region (30 gigawatts), migratory patterns of its fish, the importance of fish-friendly technology, and further studies needed to understand hydro’s impact on fish of the Mekong.

Authors of the Fisheries paper include scientists from PNNL, the National University of Laos, and the Living Aquatic Resources Research Center in Laos, the Federal University of São João Del-Rei in Brazil, the University of British Columbia; and from Australia, the Port Stephens Fisheries Institute in New South Wales, the Narrandera Fisheries Centre in New South Wales, and Fishway Consulting Services. PNNL’s work in the area has been funded by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, and AusAid, the Australian Agency for International Development.

Reference: Richard S. Brown, Alison H. Colotelo, Brett D. Pflugrath, Craig A. Boys, Lee J. Baumgartner, Z. Daniel Deng, Luiz G.M. Silva, Colin J. Brauner, Martin Mallen-Cooper, Oudom Phonekhampeng, Garry Thorncraft, Douangkham Singhanouvong, Understanding barotrauma in fish passing hydro structures: a global strategy for sustainable development of water resources,Fisheries, March 2014, DOI:10.1080/03632415.2014.883570.